|

I discovered electronics in 1963, when I was eleven,

by digging around in the stuff people put out on the curb on

garbage day, and dragging home dead radios and TVs for avid

dissection in the garage. And for years I pieced together radios

out of chassis pickins' and Fahenstock clips, guided by books like

Harry Zarchy's Using Electronics and Alfred Morgan's The

Boy's Second Book of Radio and Electronics. My best friend

Art, who lived across the alley, got into electronics a year or so

later, but he had something even better: Stacks and stacks of old

Popular Electronics magazines, given to him by his Uncle

George, who was an electrical engineer for the phone company. We

both prowled through them incessantly, looking for cool projects

to build.

We saw lots of cool projects. And before too long, we saw

ourselves there as well.

Every issue in the pile had a short fiction story in it about two

boys named Carl and Jerry, who were as obsessed with electronics

as we were, and used it to help other people, foil criminals,

impress girls, and get out of jams. The boys were a little older

than Art and I, but beyond that, the resemblances were striking:

One was thin, one chunky. One had glasses, one did not. One was

good with theory (as Art was) the other was better with tools

(me.) Every story described a concept in electronics, and most of

the time put it to work.

To Explain and Inspire

I didn't know it at the time, but Carl and Jerry had been in Popular

Electronics since the magazine's debut issue in October,

1954. John T. Frye wrote an episode almost every month for ten

years—119 stories!—until November 1964. The stories, while often

fiendishly clever, were sometimes a shade breathless but also a

little wry in a way that appealed to slightly precocious

twelve-year-old boys. They reminded me of the Tom Swift, Jr. books

that I was also reading at about that time, only with real,

basement-friendly technology instead of Swiftian half-magic

super-science. (See

my essay on Tom Swift for more about this.) As I discovered

much later, there was actually greater resemblance to the older

and more down-to-Earth Tom Swift Sr. books, like Tom

Swift and His House on Wheels. (Egad! Tom Swift

invented the RV!) As John Frye was most likely twelve years old

toward the end of the Tom Swift, Sr. era, this isn't surprising.

The language was amazingly similar, right down to the ubiquitous

said-book-isms:

"Ok, let's get on with

it," Carl prodded.

"Holy cow!" Jerry

breathed. "That was a tornado!"

The characters in the stories murmured, demanded, howled,

insisted, commanded, drawled, scoffed, and did almost everything

but "said." But talking about flaws in the fictional techniques

misses the whole point: The stories were there to explain things,

and to inspire us to emulate Carl and Jerry's curiosity and

ingenuity by working with electronics ourselves.

As with the Tom Swift books, each story revolved around a science

or technology concept. Occasionally the entire story was a dialog

between the boys, one asking questions and the other lecturing.

("TV Antennas" from August 1955, and "The Bell Bull Session" in

December 1961 are good examples.) But more often than not, the

boys build an interesting gadget, explaining along the way how it

worked, and then put it to use in a clever fashion. Perhaps the

crispest example is "Lie Detector Tells All" in November 1955. The

boys build a lie detector (explaining the principles behind it)

and test it on Jerry's parents. Mr. and Mrs. Bishop are both

caught up in "little white lies" in front of one another, and then

each quietly approaches the boys later on and offers them ten

dollars to dismantle the machine!

The stories span the whole universe of what hobby electronics was

about at the time: Ham radio, sonar, metal detectors, Hi-fi audio,

tape recorders, remote sensors, radio controlled models, and so

on. Nor did Frye cling to the past: When the world's first

transistor radio appeared in 1955, Carl and Jerry had one almost

immediately, and used it to track a tornado. ("Tornado Hunting by

Radio", May 1955.)

Frye cited experts in the real world, occasionally with

references to science and technology journals. He made semiregular

mention of projects and articles that had recently appeared in Popular

Electronics, often as the major basis for the story at hand.

In the February 1961 issue, for example, he made good use of the

cover-story gizmo: the Infraphone, a sort of walkie-talkie that

encoded voice on a beam of infrared light. Working with police,

they used a pair of Infraphones to foil a gang of thieves who were

monitoring police radio frequencies and thus eluding capture.

The Carl and Jerry stories have been criticized for being a

little too glib, and making electronics sound easy. One thing that

not everyone remembers is that the boys occasionally taught us

that not all projects work out. In "The Meller Smeller," (January

1957) the boys attempt to use an electrostatic filter to remove

odors from the air. They basically attempt an electronic gas mask,

and then have the bad karma to test it for the first time on a

skunk. It didn't work. They buried their clothes in the backyard.

Not all of the stories are "adventures" in any sense of word. As

I mentioned above, many are simple dialogs between the boys, as

they build or troubleshoot some sort of device. This may have been

necessary at times. 2,500 words is not a lot of room to

move! In "Tussle with a Tachometer" (July, 1960) they build a tach

for their car, from scratch, and explain how it works and how to

calibrate it. There's no adventure, but once you read it you'll

have a very clear sense for how automotive tachometers of that era

functioned. The adventure came in a couple of issues later, in

"Tick-Tach-Dough" (September 1960). The boys attach a tape

recorder to their homebrew tach to test its calibration. Their car

is stolen by bank robbers, who stash what they took from a bank

somewhere and won't say where. Carl and Jerry play detective, and

use stereo headphones to play the tach recording into one ear

while listening to the real tach in the other, to retrace the

vehicle's speed and acceleration in order to find the stolen cash.

Brilliant—but incomprehensible if you don't know how tachometers

work. Clearly, Frye had to tell the first story (how tachs work)

to be able to use a hacked tachometer to solve a crime in a later

story.

Could They Really Do That?

Something that Art and I often wondered is whether the technology

tricks Frye built his stories around were feasible. We often asked

one another: Would that really work? Many of them were no

great challenge, especially in the first few years of the series.

Using a solenoid-triggered camera to catch a henhouse thief (as

the boys did in June, 1956) almost seemed too easy to us. Later

on, as Frye hit his stride, the stories became cleverer, and the

technology a lot subtler. Strapping a theremin to your back to

provide a kind of audio biofeedback as you practice basketball

free-throws ("Therry and the Pirates," April, 1961) would be

breathtakingly brilliant—if it worked. Alas, we had no way to know

short of building a theremin ourselves and trying it.

Another brilliant invention was Jerry's "infrasonic" microphone

in "A Low Blow," March, 1961. The device resembled an aneroid

barometer, consisting of a thin sheet of spring brass glued over

the open end of a mayonnaise jar. The capacitance between the

brass sheet and a steel plate inside the jar changed as variations

in air pressure (as by extremely low frequency sound waves) flexed

the brass sheet, and the changing capacitance pulled the frequency

of an audio oscillator. Placed at the end of a long run of

about-to-be-buried natural gas pipes out in the street (for noise

reduction) the device reported the subsonic emanations of a small

tornado in the moments before the tornado scattered the pipe

sections and destroyed the infrasonic mic. That story made me

absolutely crazy to build one, but I wasn't quite sure

where to begin. I was only 12, just beginning to understand

electronics, and too poor to afford the sort of test gear that

Carl and Jerry took for granted. But I never doubted for a

millisecond that the device would work, and I ached to be good

enough at the craft to build things like that.

Even at its wildest, Carl and Jerry's technology remained just

this side of outrageous, and while a degreed electrical engineer

might quibble with the gadgetry, Art and I were still 12-year-old

newbies who had no clue. What did occasionally make us roll our

eyes were the preposterous situations that Carl and Jerry found

themselves in, and the remarkable coincidences that allowed them

to prevail, especially when they got into trouble. Once, when they

were trapped by a load of coal dumped into the high school coal

bin, ("A Nickel's Worth," March 1958) they signaled for help by

tapping into the school PA system through a cable running through

the rafters in the little room they were stuck in—using a

transistor audio oscillator that Carl just happened to

have in his pocket, powered by a cell made of coins and paper

moistened with spit.

This Oh Come On factor was a little strong at times, as

was the Haven't We Heard This One Before? factor. Getting stuck

somewhere and signaling for help in peculiar ways (always using

Morse Code) became a Carl and Jerry standard. Making a spark

transmitter from a broken model airplane—kewl! Doing the same

thing with an outboard motor, well, sure. Escaping from underneath

an overturned car by making a spark transmitter out of the

ignition coil, OK. Using Morse Code smoke signals to escape from

murderous bootleggers...c'mon awready. Been there! Done that!

Sure, we rolled our eyes—but we kept watching the mailbox for the

next issue, just the same. And with the perspective of forty years

of hindsight (and having read about 100 of the stories within the

past two weeks) I have to admire the way that John Frye covered

virtually the entire universe of hobby electronics of his day,

which was much narrower than ours is now. Small wonder he

repeated himself a little—and I grin a little to wonder what he

would be able to do if he were alive and writing today!

Evolving Characters

Like any good fictional series, especially one targeted at young

people, the Carl and Jerry canon contains a cast of accessible

characters and uses them quite consistently over the years. In

addition to Carl and Jerry themselves, we meet:

- Bosco, Carl's dog (said to be an airdale but mostly looking

and acting like a mutt);

- Eight-To-Go, a black cat that the boys barely rescue from an

oil drum sunk to the bottom of a flooded quarry, hence his

name—one of nine lives down, eight to go...

- Police Chief Morton, who is both exasperated with the boys'

exploits and dependent on them to solve crimes;

- Mr. Gruber, an elderly man down the street who rode with Teddy

Roosevelt's Rough Riders but is obsessed with flying saucers and

science fiction;

- Norma, a girl living next door who (at 22 or 23) is a little

too old to be a romantic interest to the boys but who looks to

them to help her with her love life;

- Mr. Stagg, the clueless high-school principal;

- Jodi Preston, a coed and ham radio op studying EE with the

boys at Parvoo University; and

- Thelma, a friend of Jodi's at Parvoo, about whom we don't in

truth learn much, but who may exist to keep the boys from

fighting over Jodi!

Most of the stories take place in and around Carl and Jerry's

small-town home in northern Indiana, though with geological

features like caves and hills that one just doesn't associate with

Midwestern corn country.

Unlike Tom Swift and most of the characters in the Sunday comics,

Carl and Jerry grew up over the years. The very first stories make

them sound quite young, perhaps thirteen or at most fourteen. By

May 1959, the story states that the boys are 16. They got around

entirely on their bikes until their respective fathers agreed to

allow them to share a car in the June 1960 story, "Two Tough

Customers," which may have less electronics in it than any other

story in the series. (It does explain how to buy a used car

sensibly.) They finally graduate from high school in June, 1961.

In "Off to a Bad Start" (September 1961) the boys arrive at

Parvoo University (a thinly veiled reference to Purdue) and bemoan

the fact that they don't have their electronics lab with them.

They try to decide whether they can improvise an intercom for a

prank (which almost gets them in serious trouble) and while they

can round up parts by dumpster diving, doing the assembly is a

problem. But no: Carl remains very true to himself, and pulls a

tiny pencil solding iron and some solder from his travel case,

saying:

"You may get old Carl

away from home without his wallet, his toothbrush, or even his

pants, but you're not going to get him away without some kind

of soldering iron," he boasted.

It's intersting to watch Carl and Jerry's attitude toward girls

evolve over the years. In early stories, they sound more like

fifth graders who consider girls to have cooties, and squirm when

Norma kisses each on the cheek to thank them for saving her from

an eccentric suitor. Their relationship with Norma is intriguing

all by itself. It begins with helpful politeness (see "Ultrasonic

Romance", July 1955) but by the late 50s there is an undercurrent

of sexual tension among the three that made me grin. This scene

(from "Parfum Electronique", July 1958) is funny enough to

reproduce whole:

"I think the girl

needs a little gentle persuasion," Jerry said quietly to Carl

as they both rose to their feet.

"Right!" Carl

exclaimed as he grabbed both sides of the hammock and brought

them together over the top of Norma. He held them in place in

spite of Norma's shrieks, struggles, and threats, until Jerry

fastened them together with two huge horse-blanket pins that

had been clipped around the hammock ropes. Then the boys stood

at each end of the hammock and tugged alternately at the ropes

to bounce and toss the pinned-in girl wildly about.

"Stop! Stop!" she

finally gasped. I'll do it! And if you've messed up my

permanent, I'm going to kill you both."

"Ah, Norma," Carl

said, unfastening the pins and grinning down at the tousled

but very pretty girl; "from now on you will always be our

favorite pin-up!"

Genuine stirrings of affection for the other sex begin to show up

in late 1958, even if the boys sometimes strive mightily to deny

them. In "Vox Elektronik" (September 1958) Carl takes up

ventriloquism because a girl named Linda seems to appreciate it

when performed by a local boy named George. When it becomes clear

that he has no talent for it, Carl gets the idea that they could

put a little radio receiver into his dummy Splinter, and even rig

solenoids to work the dummy's jaw in response to the received

sound. Jerry sees through Carl's motives, however, and is dubious:

“Frankly, Carl, I

take a dim view of the whole business. I thought we both felt

the same way about girls: There will be plenty of time for

them later, but right now you and I can have lots more fun

with electronics.”

“I know,” Carl said

miserably; “but I still can’t stand being made to look like a

dope in front of Linda—at least not by a porch-swing poodle

like George."

The real lesson comes later: After Splinter cons Linda and George

completely, Linda responds a little too enthusiastically, and

Carl, now tormented by conscience as well as concern that a girl

was becoming stuck on him, explains to them what he's done and

slinks home again.

Frye has some further fun with Carl and girls in the December

1958 story "Under the Misteltoe." The boys are invited to a teen

Christmas party, but they know that a local hussy plans to steer

Carl under the misteltoe and demand a kiss. The boys concoct a

plan to deliver a slight shock to Cindy from a 130V battery and a

current-limiting resistor at kiss-time, and thus dampen her ardor.

Unfortunately, Jerry's geek-girl cousin Pat overhears the plot and

hatches a counterplot: Rigging Cindy with an identical 130V

battery with the polarity turned the other way! (The two batteries

buck and thus no current flows.) Expecting to shock Cindy with a

quick kiss, Carl finds that nothing happens. Assuming a loose

wire, he prolongs the kiss while trying to reconnect the wire, and

ends up the red-faced victim of catcalls and wolf-whistles from

the other partygoers, basically getting the opposite effect from

what he intended.

Electronics-savvy Cousin Pat prefigures a new character who

appears soon after the boys go off to Parvoo: Jodi Preston, a

southern belle in Parvoo's EE program with a drawl and a ham

license. The boys use their wizardry to help Jodi much as they

helped Norma, but this time Carl and Jerry have no excuses;

they're college boys and old enough to go out on dates. Frye

introduces a second girl, Jodi's friend Thelma, but says little

about her, and one gets the sense that she's there to balance the

slate. By November 1963 Carl, Jerry, Jodi, and Thelma were a

foursome, but there just isn't the goofy warmth among them that

John Frye created between the boys and Norma.

As little as we actually know about John T. Frye himself, it's

possible to find little glimpses of the man here and there in how

his characters act and what they say. Frye certainly made his

feelings known about liberal arts types at the end of "Wrecked By

a Wagon Train" (February, 1962) when the boys help nab a student

from "a liberal arts university" in the southern part of Indiana

who was robbing fraternities at Parvoo. Jerry says:

"You know,

electronics was a nemesis for that poor guy. Electronics put

the finger on him in the first place, and then a TV wagon

train wrecked his alibi. His second mistake was

transferring his operations from a liberal arts university to

one with a strong accent on electronics."

"Well, you wouldn't

expect a guy dumb enough to make the first mistake of starting

to steal to be very bright," Carl muttered sleepily.

Maybe it was just the university. (Indiana State?) In "Substitute

Sandman" (November, 1961) Carl tells us:

"Our English teacher

says that education is the process by which a person moves

from cocksure ignorance to thoughtful uncertainty. Some folks

are hard to move."

Heh!

Evolving Art

As effective as John Frye's stories were, they might not have

grabbed their intended audience quite so viscerally if the

magazine's artists had not gotten the boys' physical appearance

down almost exactly right. There were illustrations

associated with every single story, and over the years, the

picture of tall, lean Carl beside shorter, stockier Jerry was

burned into the mythic memory of their loyal fans.

It didn't happen immediately...but close, close. When PE's staff

artists first drew the boys in the magazine's debut issue, Jerry

came off as a lazy-looking, unlikeable little brat, with a face

that did not suggest the high intelligence that Frye had given

him.

Carl, on the other hand, became more realistic over time but did

not change substantially until the very last year of the series.

The "Far Side" glasses (which were mainstream back then—my wife

wore them in the early Sixties and thought they were cool!) and

blonde pompadour remained with Carl until late 1963. It didn't

help that the early issue illos were drawn mostly as cartoon

archetypes. It was too easy to present Jerry as the iconic "little

fat boy."

PE

quickly realized its mistake, and gave Jerry a radical makeover

with the April 1955 issue. (Perhaps PE got a few too many letters

of complaint from "little fat boys.") Jerry remained shorter and

fatter than Carl, but he was at least a little more buff and now

had an intelligent and likeable face, looking much more like a

teenage slide rule jockey and less like a juvenile delinquent with

an IQ of 77. The boys were now drawn older as well, moving from

early teens to senior high. PE

quickly realized its mistake, and gave Jerry a radical makeover

with the April 1955 issue. (Perhaps PE got a few too many letters

of complaint from "little fat boys.") Jerry remained shorter and

fatter than Carl, but he was at least a little more buff and now

had an intelligent and likeable face, looking much more like a

teenage slide rule jockey and less like a juvenile delinquent with

an IQ of 77. The boys were now drawn older as well, moving from

early teens to senior high.

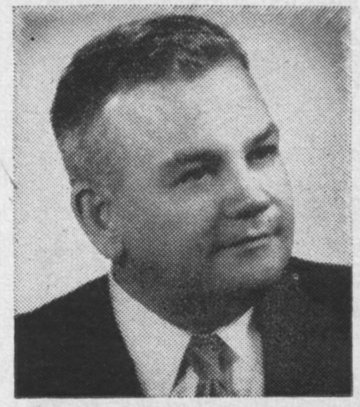

I find it interesting that the redesigned Jerry looks a great

deal like a teen-aged version of the adult John T. Frye, as shown

in a 1951 photo published in

the Logansport newspaper in 1951 and later in 1962.

The quality of the art for the series was always a little uneven.

As a former magazine editor, I can guess why: The staff artists

may not have been given their assignments until the issue had been

laid out, and the editors knew how much space remained for art

after the articles and ads were "in flats." (They may also have

been technical artists with more experience in schematics than

cartooning.) There was almost always at least one drawing, but

there were sometimes as many as four, and the drawings varied

widely in size and (sometimes) shape. Knowing the tight schedule

of a monthly magazine, it's not impossible that the artists had as

little as an hour or two to knock out a story's illos. It may be

that the clumsiest drawings were last-minute demands: "McGuffin

Radio just canceled their ad, so we have another three

column-inches to fill in Carl and Jerry. You've got half an hour.

Get cracking!"

This July, 1955 depiction of Bosco and girl-next-door Norma may

count as the worst illo of the series. I wonder if it was one of

those quarter-to-midnight emergency jobs, dashed off in ten

minutes by an exhausted art staffer who just wanted to go home.

In May of 1959, the boys got a design tweak, which coincided with

the magazine itself moving from a rougher newsprint to a smoother,

coated paper. The smoother paper allowed the use of finer halftone

screens and a much more nuanced art style. Carl and Jerry went

into slightly softer focus but became a lot more realistic, and

the story-header image below (which was used for almost three

years) is how most people remember them today. The new Jerry,

while still slightly rounder than Carl, could no longer even

remotely be considered "fat." (Every so often an artist drew Jerry

with an anomalous tummy—except for the boys' faces, art design

consistency among the stories was spotty.)

The boys got one last art makeover in the November, 1963 issue,

by an artist who had clearly cut his teeth on fashion catalogs, or

maybe cigarette ads:

The magazine dropped the standard story header entirely, and the

art treatment changed with almost every issue. Toward the end of

1964, the single opening illustration was generally the only

illustration there was, when in earlier years there were as many

as five. The boys were now a pair of fully adult Sunday sales

insert mannikins, with neither charm nor any suggestion of the

teenage geekiness that elevated them to hero status among boys who

had looked "just like them."

(Does anybody else find the depictions of Jodi and Thelma in the

foreground here just a little bit creepy?)

This final artwork faux pas didn't matter much; by then

those of us who loved the boys knew precisely what they looked

like. It was the artist who had it wrong. They looked like us,

and had for nine years. Nothing ever would (nor ever could) change

that!

Did It Work?

In creating Carl and Jerry, John T. Frye drew on an ancient and

now mostly lost literary form: didactic (tutorial) fiction. How

well he drew characters and situations is less important than

whether we remember the lessons, forty-odd years later. I know

that I do. Having read "The Lightning Bug" (November, 1963) I

pulled the March 1962 issue from Art's stacks and built "Emily,

the Robot with the One-Track Mind" and won First Prize at our

eighth grade science fair. The Emily article explained how it

worked, but I already knew the general principles, courtesy Carl

and Jerry.

A fair number of people my age and older have written to me over

the years, generally in response to my own tutorial books like Complete

Turbo Pascal and The Delphi Programming Explorer,

and when we spoke of Carl and Jerry, many indicated that it was

the boys who had pushed them "over the edge" into careers in

science and technology. One gentleman, a now-retired EE, said

this: "They made it sound maybe a little too easy, but that just

made me work harder so I could succeed like they did. It worked."

Boy, did it ever.

(John Frye's QSL card, courtesy Bob Ballantine

W8SU.)

|

|

|

|

| A

New Company Is Launched |

|

Carl meets Jerry, who

solves a ham radio antenna problem for him.

|

| October 1954: V1 #1 |

| A

Light Subject |

|

The boys discuss

photoelectricity and Jerry demonstrates a photocell.

|

| November 1954: V1

#2 |

| The

Hot Dog Case |

|

Carl's dog comes home

with radioactive paws, and the boys track him by radio.

|

| December 1954: V1

#3 |

| Operation

Startled Starling |

|

The boys tape record a

bird's distress cry to scare away some starlings.

|

| January 1955: V2 #1 |

| Two

Detectors |

|

The boys use 2M HTs to

eavesdrop on what they think is a murder.

|

| February 1955: V2

#2 |

| Going

Up, Up, Up |

|

Will TV signals bounce

off a silver-painted balloon? Maybe...

|

| March 1955: V2 #3 |

| The

Attraction of Ham Radio* |

|

Carl talks about ham

radio to Jerry, in preparation for a school speech.

|

| April 1955: V2 #4 |

| Tornado

Hunting by Radio* |

|

The boys use a

directional TV antenna to track a storm, and spot a

tornado.

|

| May 1955: V2 #5 |

| How

TV Works* |

|

Using a garden hose and

the garage wall, Jerry explains how TV works.

|

| June 1955: V2 #6 |

| Ultrasonic

Romance* |

|

Jerry devises an

ultrasonic mosquito killer to help the girl next door.

|

| July 1955: V3 #1 |

| TV

Antennas* |

|

On a hike, Jerry explains

how different kinds of TV antennas work.

|

| August 1955: V3 #2 |

| Electric

Shock* |

|

Jerry gets a bad shock

from a faulty radio, and explains the dangers of 117V.

|

| September 1955: V3

#3 |

| The

Great Bank Robbery |

|

Clever use of a 2M

transceiver foils a bank robbery.

|

| October 1955: V3 #4 |

| Lie

Detector Tells All |

|

Jerry subjects his

parents to his home-made lie detector.

|

| November 1955: V3

#5 |

| Santa's

Little Helpers |

|

The boys build a talking

Santa figure for the front lawn to amuse local kids.

|

| December 1955: V3

#6 |

| Trapped

in a Chimney |

|

The boys create a spark

transmitter to escape from an old smokestack.

|

| January

1956: V4 #1 |

| How

to Haunt a House |

|

A man hires Carl &

Jerry to "haunt" a house he owns with gadgetry.

|

| February 1956: V4

#2 |

| Electronic

Trap |

|

Jerry's proximity relay

alerts him to a burglar in the basement.

|

| March 1956: V4 #3 |

| Gold

Is Where You Find It |

|

The boys find an old

farmer's gold watch with a metal detector.

|

| April 1956: V4 #4 |

| Feedback |

|

Jerry teaches Carl about

negative feedback while listening to birds.

|

| May 1956: V4 #5 |

| Geniuses

at Work |

|

The boys rig a camera in

a henhouse to catch an intruder on film.

|

| June 1956: V4 #6 |

| Anchors

Aweigh |

|

Jerry's radio-controlled

tugboat rescues a man from a boating accident.

|

| July 1956: V5 #1 |

| Bosco

Has His Day |

|

Carl's dog Bosco learns

to retrieve with some help from a tiny radio receiver.

|

| August 1956: V5 #2 |

| Electronic

Beach Buggy |

|

An RC wagon carrying

Jerry's metal detector foils a counterfeiting ring.

|

| September 1956: V5

#3 |

| Abetting

or Not? |

|

The boys' 2.4 GHz radio

interferes with the local police radar speed trap.

|

| October

1956 V5 #4 |

| Eeeelectricity! |

|

Jerry explains to Carl

how electric eels generate electricity.

|

| November 1956: V5

#5 |

| Extra-Sensory

Perception |

|

The boys build a covert

radio transceiver and fake psychic powers.

|

| December 1956: V5

#6 |

| The

"Meller Smeller" |

|

An attempt to remove

odors with high voltage fails spectacularly.

|

| January 1957: V6 #1 |

| Electronic

Cops and Robbers |

|

The boys bust a car-theft

ring with radio direction-finding gear.

|

| February

1957: V6 #2 |

| The

Secret of Round Island |

|

A radio-triggered camera

on a kite reveals a bootlegging operation.

|

| March 1957: V6 #3 |

| Strange

Voices |

|

A neighbor's wireless

headphones bleed into the boys' VLF loop antenna.

|

| April 1957: V6 #4 |

| "Holes"

to the Rescue |

|

A transistorized SW

converter allows the boys to call for help on 10M.

|

| May 1957: V6 #5 |

| Out

of the Depths |

|

While recording fish

sounds in an old quarry, the boys rescue a cat.

|

| June 1957: V6 #6 |

| Brain

Waves |

|

Jerry tries to read

Carl's brain waves, and reads the wall clock instead.

|

| July 1957: V7 #1 |

| A

Crusoe Caper |

|

Lost in a storm, the boys

call SOS using the magneto of an outboard motor.

|

| August 1957: V7 #2 |

| Electronic

Shadow |

|

C&J's homebrew

radio-equipped gyrocompass foils a bank robber.

|

| September 1957: V7

#3 |

| The

Cat Gets a Treatment |

|

The boys use a CB

transmitter as a diathermy machine to help their cat.

|

| October 1957: V7 #4 |

| The

Demonstration |

|

The boys "enhance" a

Wimhurst machine with a hidden Tesla coil.

|

| November 1957: V7

#5 |

| Santa

Knows All |

|

Carl and Jerry rig a

hidden transmitter for a department-store Santa.

|

| December 1957: V7

#6 |

| Cupid

and the Ions |

|

A mood-boosting ion

generator makes Norma's boyfriend's hair stand on end.

|

| January 1958: V8 #1 |

| Electronic

Detective |

|

The boys plant a

miniature transmitter in a cap gun to nab a young

shoplifter.

|

| February 1958: V8

#2 |

| A

Nickel's Worth |

|

A coin cell allows the

boys to signal for help when they're trapped in a coal

bin.

|

| March 1958: V8 #3 |

| Little

Drops of Water |

|

A moisture sensor, a

window closer, and a water pistol nab a second-story

man.

|

| April 1958: V8 #4 |

| Fish-Sniffing |

|

A fish with an ultrasonic

tag helps the boys find a school of bluegills.

|

| May 1958: V8 #5 |

| The

Tele-Tattletail |

|

Jerry's lashup telemetry

system keeps two small boys from learning to smoke.

|

| June 1958: V8 #6 |

| Parfum

Electronique |

|

An electronic odor

generator drives off yet another of Norma's boyfriends.

|

| July 1958: V9 #1 |

| Cow-Cow

Boogie |

|

A radio-equipped,

booze-loving cow helps nab a gang of bootleggers.

|

| August 1958: V9 #2 |

| Vox

Elektronique |

|

Carl overly impresses a

girl with a radio-assisted ventriloquist's dummy.

|

| September

1958: V9 #3 |

| Too

Close for Comfort |

|

Jerry's RC plane carries

a rescue line to swimmers trapped in a flooded river.

|

| October 1958: V9 #4 |

| Command

Performance |

|

A neon sign transformer

adds some sparks to a sword fight in the Latin Club

play.

|

| November 1958: V9

#5 |

| Under

the Misteltoe |

|

Carl's shocking 130V

anti-misteltoe scheme backfires—and he gets kissed!

|

| December

1958: V9 #6 |

| Little

"Bug" with Big Ears |

|

The boys create a

sensitive phone bug to help police nab a kidnaper.

|

| January 1959: V10

#1 |

| He

Went That-A-Way |

|

A 1-way gate keeps a

skunk from living under Carl's house—and starts a fight.

|

| March 1959: V10 #3 |

| How

I Wonder What You Are |

|

The boys rig a fake

satellite to show Mr. Gruber that his eyes are still OK.

|

| April 1959: V10 #4 |

| "BBI" |

|

The boys turn a cheating

baseball team's technology against them.

|

| May 1959: V10 #5 |

| Dog

Psychologists |

|

The boys use Bosco's

radio training cap to teach him to hunt mushrooms.

|

| June 1959: V10 #6 |

| The

Blubber Banisher |

|

Norma uses the boys'

shock-mode exercise timer to repel a masher.

|

| July 1959: V11 #1 |

| Away

From It All |

|

The boys fix a game

warden's radio and help nab a pair of illegal

spear-fishers.

|

| August 1959: V11 #2 |

| The

Surrogate Mother |

|

The boys build an

automated nursing box to save a pair of orphaned

puppies.

|

| September 1959: V11

#3 |

| Out

of the Shadow |

|

The boys' cloud-speed

sensor detects a forest fire before it can spread.

|

| October 1959: V11

#4 |

| The

Ghost Talks |

|

Selsyn motors and a

glowing skull haunt a house for Norma's sorority.

|

| November 1959: V11

#5 |

| Tipsy,

Jr. |

|

A modded police speed

radar detects a thief's iceboat on a frozen lake.

|

| December 1959: V11

#6 |

| Whirling

Wheel Magic |

|

A small gyroscope on a

timer catches an unwary assembly plant thief.

|

| January 1960: V12

#1 |

| Improvising |

|

Jerry hacks a car radio

into a crude AM transmitter to call for help in a storm.

|

| February 1960: V12

#2 |

| A

Hot Idea |

|

Jerry's thermistor wind

speed meter inadvertently becomes a fire alarm.

|

| March

1960: V12 #3 |

| El

Torero Electronico |

|

Carl's RC plane distracts

an angry bull so that the boys can get away.

|

| April 1960: V12 #4 |

| The

Black Beast |

|

A remote

capacitance-operated relay reveals a cave photographer.

|

| May 1960: V12 #5 |

| Two

Tough Customers |

|

The boys buy their first

car after checking it with a contact mike.

|

| June 1960: V12 #6 |

| Tussle

with a Tachometer |

|

Carl explains how car

tachometers work, then the boys build and calibrate one.

|

| July 1960: V13 #1 |

| Electronic

Lifeline |

|

The boys' homebrew 10M

HTs help rescue a pair of greenhorn boaters.

|

| August 1960: V13 #2 |

| Tick-Tach-Dough |

|

A tape recording of a

stolen car's tach leads the boys to a stash of cash.

|

| September 1960: V13

#3 |

| The

Crazy Clock Caper |

|

The boys track down a

problem in their school's synchronized wall clocks.

|

| October 1960: V13

#4 |

| The

Hand of Selene |

|

A mannequin hand with a

radio-controlled electromagnet is a hit at Norma's

seance.

|

| November

1960: V13 #5 |

| The

Snow Machine |

|

Mr. Gruber uses a

superpower ultrasonic audio oscillator to make it

snow...maybe!

|

| December 1960: V13

#6 |

| A

Rough Night |

|

The boys' mobile rig

solves a crisis during an ice storm.

|

| January 1961: V14

#1 |

| Below

the Red |

|

An infrared communicator

helps Chief Morton catch some dope pushers.

|

| February 1961: V14

#2 |

| A

Low Blow |

|

Jerry builds an

"infrasonic" mic and uses it to listen for tornadoes.

|

| March

1961: V14 #3 |

| Therry

and the Pirates |

|

Carl straps a theremin to

his back to improve his basketball free throw.

|

| April 1961: V14 #4 |

| Operation

Worm Warming |

|

The boys attempt

underground radio transmission and get stuck in a cave.

|

| May 1961: V14 #5 |

| First

Case |

|

The boys find that a

neighbor girl's crystal set is producing TVI.

|

| June 1961: V14 #6 |

| Treachery

of Judas |

|

The boys use a hidden

microphone to help a G-Man foil a communist plot.

|

| July 1961: V15 #1 |

| Too

Lucky |

|

A boater's malfunctioning

SCR lamp dimmer is found to be shocking fish.

|

| August 1961: V15 #2 |

| Off

to a Bad Start |

|

The boys arrive at Parvoo

and rig an intercom in a mailbox for a prank.

|

| September 1961: V15

#3 |

| Blackmailing

a Blonde |

|

The boys blackmail a

trophy-stealing coed with a highly directional mic.

|

| October 1961: V15

#4 |

| Substitute

Sandman |

|

Jerry's sleep-learning

experiment is hijacked by a campus hypnosis expert.

|

| November 1961: V15

#5 |

| The

Bell Bull Session |

|

|

| December 1961: V15

#6 |

| Wired

Wireless |

|

The boys trace a

mysterious jammer of Parvoo's carrier-current AM

station.

|

| January 1962: V16

#1 |

| Wrecked

By a Wagon Train |

|

A fleeing thief is caught

by timing a TV episode of Wagon Train.

|

| February 1962: V16

#2 |

| Tunnel

Stomping |

|

The boys meet a female

ham at Parvoo while exploring the steam tunnels.

|

| March 1962: V16 #3 |

| ROTC

Riot |

|

Front-end overload of a

tape recorder humbles an obnoxious ROTC officer.

|

| April 1962: V16 #4 |

| The

Sparking Light |

|

The boys hack the campus

wolf's headlights to help their lady friend.

|

| May 1962: V16 #5 |

| Pure

Research Rewarded |

|

The boys make a telephone

out of a TV set to foil a murder plot on a judge.

|

| June 1962: V16 #6 |

| River

Sniffer |

|

A simple pH bridge

locates a source of fish-killing acid pollution in a

river.

|

| July 1962: V17 #1 |

| Electronic

Eraser |

|

A homebrew bulk tape

eraser kills a spy's tape without him knowing it.

|

| August 1962: V17 #2 |

| Clinging

Vine |

|

Jerry tests an underwater

speaker and gets tangled in wire on a lake bottom.

|

| September 1962: V17

#3 |

| Difference

Detector |

|

Carl boosts a shy girl's

status with a fake "sex appeal" detector.

|

| October 1962: V17

#4 |

| Hello-o-o-o

There! |

|

The boys use a

mechanical-readout sonar unit to find a lost plaque in

the river.

|

| November 1962: V17

#5 |

| Aiding

an Instinct |

|

Carl fakes "homing

pigeon" sense with a gadget that detects buried conduit.

|

| December 1962: V17

#6 |

| Stereotaped

New Year |

|

A stereo tape recording

brings Mr. Gruber out of his depression.

|

| January 1963: V18

#1 |

| |

|

John Frye is ill and

there is no story this issue, per a note on P. 93.

|

| February 1963: V18

#2 |

| Succoring

a Soroban |

|

Both sides cheat in a

duel between an abacus and paper & pencil

arithmetic.

|

| March 1963: V18 #3 |

| Slow

Motion for Quick Action |

|

A phono cartridge

transducer records the settling of an old wooden bridge.

|

| April 1963: V18 #4 |

| The

Sucker |

|

The boys foil a thief

using suction to open remote-operated car trunks.

|

| May 1963: V18 #5 |

| Elementary

Induction |

|

C&J's 6-meter mobile

rig detonates a bomb intended to kill a visiting

official.

|

| June 1963: V18 #6 |

| Extracurricular

Education |

|

Trapped under a car, the

boys rig a spark transmitter from the ignition coil.

|

| July 1963: V19 #1 |

| Sonar

Sleuthing |

|

C&J's paint-can sonar

unit finds a hoard of stolen cash in a flooded quarry.

|

| August 1963: V19 #2 |

| "All's

Fair-" |

|

A hacked garage-door

opener receiver helps catch a gang of car thieves.

|

| September 1963: V19

#3 |

| High-Toned

Hawkshaw |

|

C&J spot a student

using ultrasonic sound to rattle campus coeds.

|

| October 1963: V19

#4 |

| The

Lightning Bug |

|

The boys build a

bug-shaped beambot to scare Jodi's sorority pledges.

|

| November

1963: V19 #5 |

| Joking

and Jeopardy |

|

The boys'

audio-controlled submarine rescues a man who falls

through thin ice.

|

| December 1963: V19

#6 |

| The

Girl Detector |

|

A hidden thermistor at

calf-level tells girls from boys at a fraternity dance.

|

| January 1964: V20

#1 |

| Pi

in the Sky and Big Twist |

|

The boys alert a school

to a tornado by way of a flying educational TV station.

|

| February 1964: V20

#2 |

| The

Hot, Hot Meter |

|

Radioactive paint helps

nab a thief stealing meters from a defense plant.

|

| March 1964: V20 #3 |

| The

Educated Nursing Bottle |

|

The boys build a Proton

Precession Magnetometer to hunt for treasure.

|

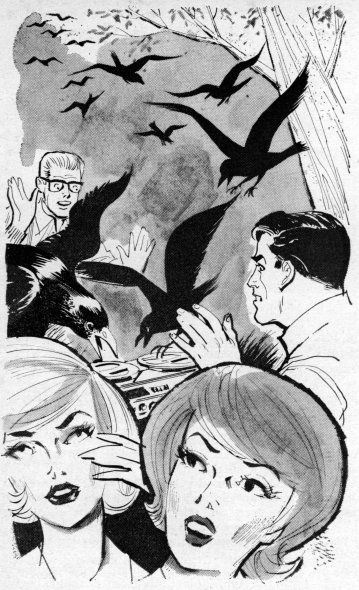

| April 1964: V20 #4 |

| For

the Birds |

|

Recorded crow distress

calls prompt an attack by a flock of angry crows.

|

| May 1964: V20 #5 |

| Togetherness! |

|

A bad flood in C&J's

home town forces hams and CBers to work together.

|

| June 1964: V20 #6 |

| Bee's

Knees |

|

An attempt to quiet a

hive of bees with a loud audio tone fails spectacularly.

|

| July 1964: V21 #1 |

| |

|

(No story)

|

| August 1964: V21 #2 |

| A

Jarring Incident |

|

The boys covertly attach

a crash beacon to a car to thwart an insurance fraud

plot.

|

| September 1964: V21

#3 |

|

|

(No story)

|

| October 1964: V21

#4 |

| The

Electronic Bloodhound |

|

A gas detector foils a

robber by detecting dry cleaning fluid on some currency.

|

| November 1964: V21

#5 |

|

|

(No story)

|

| December 1964: V21

#6 |

* Six of the stories in 1955 were not given titles

by the author or the magazine, so the titles shown here are my

fabrications, based on what the stories were about.

Above is something I've wanted to post for a long

time: A complete index of all known Carl & Jerry adventures by

John T. Frye. There are 119 in all. In the left half of the index

are the title, issue date, and volume number. In the right half

are two-line capsule summaries of each episode, so that you can

more easily spot your favorite episodes, which most people recall

by "what happened" rather than by title or issue.

The color coding is significant. As I explain below,

I'm in the process of republishing the full run of Carl and Jerry

as five anthologies, and each anthology in the series is

color-coded to the index. The cover of the first book is blue. The

cover of the second book is mauve. The cover of the third book is

yellow, and so on. The color of any given story's title in the

index tells you which volume the story is in.

I will be releasing a number of the stories as

standalone PDF documents, which may be downloaded without charge

and freely distributed. The title to these stories will be in

bold, and the link to those stories will be the issue date. If the

issue date is underlined, that means there's a downloadable PDF

behind it. Keep in mind that these PDF files are typically 2 MB in

size, so plan your download time accordingly. A new one will be

posted every few weeks, as time allows, so do check back

regularly!

As well-known as he was among those who grew up reading his

articles, little has ever been written about John T. Frye himself.

Setting this right has taken more time and more work than I had

expected, and I want to thank several people for digging around

and locating what data there is, especially Michael Holley and Bob

Ballantine W8SU.

US Census records tell us that John Frye was born in Poinsett

County, Arkansas on March 14, 1910. He was the second son of Orton

P. and Essie Frye. His older brother Parker was born in 1905.

Orton Frye was listed as owner of a sawmill in 1910, and in 1920

owned a machine shop in West Prairie, Arkansas, with his son

Parker working there with him. The 1930 census shows the Frye

family as moved to Logansport, Indiana, and living at 1810

Spear St., the house where John lived, as best we know, for

the rest of his life. (The 1940 census records are still sealed,

and will not be released until 2012.) Orton P. Frye is not shown

in the Social Security Death Index, and it may be that he died

before the Social Security system was put in place in the late

1930s. Essie lived to be 91, and died in 1974. Parker A. Frye died

in 1971 in Park Ridge, Illinois, where he had lived for some time.

No evidence has ever come to light indicating that Frye married or

had children.

Quite a few Fryes lived in west-central Indiana, and some even in

Logansport. This has caused some confusion: There was another John

T. Frye living in Camden, Indiana, from 1932-1976, and Camden is

only fifteen miles from Logansport. This other John T. Frye

married in 1955 and had two sons. Several people wrote to tell me

that John Frye had a brother, Samuel Bailey Frye, in Logansport,

as well as a sister Eunice. Bailey was a ham (WA9OWH) and died

only recently (2008) at age 90. However, Bailey's

obituary does not mention John T. Frye, nor do the census records

include Bailey in John Frye's family, so we can only assume he was

unrelated, or perhaps a cousin. (Ditto Eunice.)

Amazingly, he spent virtually all of his life in a

wheelchair due to a battle with polio when he was eighteen months

old,

and was never able to walk. The disease also affected his left

hand,

which he could use only imprecisely, and with difficulty. His

father

(who was a machinist) built a very maneauverable three-wheeled

scooter

out of a girl's tricycle, and John used that to get around his

small

and presumably crowded house for many years—the photo below shows

John

in the scooter when he was 66. He had several cars fitted out with

hand

controls and did a great deal of traveling around the United

States. We

know that he had a 1963 Olds Dynamic 88; legend holds that he

favored

Buicks, but we do not have confirming data at this time.

(The photo is a screen capture of a microfiche scan

of a 1976 newspaper halftone, so alas, only so much can be done

with it!)

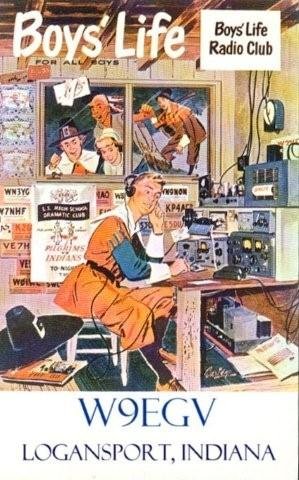

Frye was licensed as W9EGV in the 1920s, and graduated from

Logansport High School in 1930. Most people have assumed that he

attended Purdue University because of Carl & Jerry's college

career at fictional Parvoo, which shares details with Purdue in

only the thinnest disguises (like the Moss-Ade Stadium instead of

Purdue's Ross-Ade Stadium) and sometimes, as with the

Purdue/Parvoo radio station WCCR, no disguise at all. But as best

we know, he never attended Purdue, and in fact did not study

engineering at all. He did attend Indiana University, Columbia,

and the University of Chicago at one point or another, studying

psychology, journalism, history, and English. We do not know

whether or where he obtained a degree.

Studying journalism and English clearly paid off. Frye was a very

prolific contributor to the electronics and amateur radio

magazines, with supposedly 600 short pieces to his credit. The

earliest published works I've seen in the literature are a series

of short humorous items (titled "Phone Band Funnies") in QST

beginning August, 1947. However, he supposedly first appeared in

Gernsback's seminal Short Wave Craft (ancestor of Radio-Electronics)

in the early 1930s. (The

magazine's covers are classics.) He began writing a column

called “Mac’s Service Shop” in Radio & Television News

in April 1948, and it ran in one magazine or another (including Electronics

World, another Ziff-Davis publication) for 28 years, until

June, 1977. There are superficial resemblances between "Mac's

Service Shop" and Carl and Jerry: The column is nominally fiction,

in which "Mac," the owner of a radio and TV service shop, talks

about both the technical and business aspects of the radio/TV

service business to other people, often his sole and slightly

clueless employee, Barney. However, there is no "adventure" and

the action doesn't typically move beyond the shop. For a sample of

"Mac's Service Shop" in its later years, you can see scans of the

August 1975 column hosted here.

In addition to his short articles, John Frye wrote a couple of

very popular books on radio and servicing:

- Basic Radio Course (Gernsback Library #44) first

published in 1951, revised in 1955 and 1962, and reprinted by

Tab at least as late as 1977.

- Radio Receiver Servicing, 1960.

Copies of these come up on Amazon and ABEBooks regularly, and if

you collect or restore old radios they are well worth having. They

are not especially rare, and I paid about $10 each for nice clean

hardcovers. Basic Radio Course is a excellent overview of

AM radio tech circa 1950, well-written, and printed on a coated

paper that has survived well without yellowing or getting crumbly.

The 1962 edition adds some limited coverage of solid state theory.

Interestingly, my research has not shown a copyright renewal for

either Basic Radio Course or Radio Receiver Servicing,

and so their copyrights have probably expired and both have now

passed into the public domain.

From his writing it's clear that Frye knew the radios and TVs of

his era inside and out, but I've been unable to determine where he

learned the service trade, nor whether he worked in the service

field. We have no evidence that he owned his own service shop, but

from his nearly thirty years of Mac's columns it sure sounds

like he did!

A good many of the details we know about Frye's life are

summarized in a short 1962 article

in the Logansport newspaper announcing the release of an updated

edition of Basic Radio Course. (The photo was actually

taken in 1951, and appears in another short article announcing the

release of the book's first edition in that year.) Many thanks to

Lisa Enfinger for passing a scan of this along to me. Doesn't Frye

look a lot like a grown-up Jerry in the photo?

Lisa also provided a clue as to why Frye patterned Parvoo

University on Purdue: Her parents were very close friends of

Frye's, and both studied chemistry at Purdue in Frye's era. Frye

maintained a lively correspondence with both William and Margie

McCaughey for many years, and probably visited them while they

earned their degrees at Purdue in the late 1940s. Even after her

parents moved to Tucson to teach at the University of Arizona, her

mother (and Lisa too) would return to Logansport in the summers to

visit, and then spent a fair amount of time with John, who would

take young Lisa to the park on the Eel River in Logansport and buy

her rides on their merry-go-round. Lisa's great-grandparents lived

right across the street from Frye, on Spear Street in Logansport.

Her father,

Dr. William. F. "Mac" McCaughey, K7CET, may have been the

namesake of the narrator of Mac's Service Shop. Lisa's mother's

uncle, Eugene Buntain, was a classmate of Frye's at Logansport

High School. The two discovered electronics and ham radio at the

school and were close friends; Lisa wonders if Uncle Gene were the

inspiration for Carl.

Why did Frye stop writing "Carl & Jerry"? A couple of

old-timers have hinted that he had had a falling-out with the

editors at Popular Electronics toward the end of 1964.

This is suggested by the fact that he began publishing a lot of

articles in PE's main competitor, Electronics Illustrated,

early in 1965. I do not have all issues of EI from that era, but

Frye appeared in the July 1964 issue with "A Basic Course in

Vacuum Tubes." From 1965 into late 1967 he was in most issues of

EI with a couple of multipart tutorials: "The ABCs of Radio"

beginning in September 1965, and "The ABCs of Color TV" beginning

in January 1967. The last issue I have in which Frye appears is

September, 1967—which is also when my subscription to EI expired.

I have a handful of issues from 1968, and Frye does not appear in

any of them, nor does he appear in any issues of Popular

Electronics after that. "Mac's Service Shop" ran until 1977,

but Frye's other writing seems to have ceased ten years earlier.

John T. Frye died in January, 1985, at his home in Logansport.

As always, I'd love to hear from you if you have additional

details about John T. Frye's life and work beyond what I've posted

here.

Back in 2006, I tried to locate a few of my favorite

Carl and Jerry adventures, and discovered that old back issues of

Popular Electronics are not easy to come by, and not always

cheap. Being a technical book publisher in my day job, I had the

notion that an anthology of Carl and Jerry stories would be a good

thing to put together, before the old magazines either crumbled to

dust or ended up in landfills as their owners passed on. After

all, the first Carl and Jerry story—in the very first issue of Popular

Electronics—is now over half a century old. Time flies when

you're down in the basement building things, sheesh.

So I located the owner of the Carl and Jerry

copyrights, and obtained permission to republish them in anthology

form. As I cornered an ever-larger pile of the magazines on eBay,

I realized that a single book would not do it. There are 119

stories in all, representing close to 250,000 words and 300

illustrations. The five anthologies together will include every

Carl and Jerry story by John T. Frye, including all the original

illustrations. The stories will be published in chronological

order, by issue date. In general, there are two years' worth of

stories in each volume. The final volume contains a "topic index"

to all 119 stories, plus two brand new stories by long-time Carl

and Jerry fans.

All five books are now available, and may be ordered

from Lulu.com. Click on the book volume links below to order.

Available

now: Available

now:

Volume 1:

1954-1956

Available

now: Available

now:

Volume 2: 1957-1958

Available

now: Available

now:

Volume 3: 1959-1960

Available

now: Available

now:

Volume 4: 1961-1962

Available now: Available now:

Volume 5: 1963-1964

Note: The anthologies are printed and sold one at a

time by print-on-demand technology, and thus will not be available

from bookstores. Alas, this means that you can't order them

"overnight" as the Lulu system takes between 3 and 5 days to

manufacture each book before the book is shipped.

|